A WWII DESTROYER: THE FARRAGUT

BY DONALD L. FISCHER

[We remember the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, as Donald Fischer shares his experiences. KH]

As a teenager, the Navy was of interest to me. I dreamed of exotic places and had a lust for adventure. But it was only a young man’s dream. The odds were pretty much against such an experience. After all, I had a happy family life and Iowans were supposed to be farmers; little did I know.

After I graduated from high school in my hometown of Walnut, Iowa in 1938, I had found a job with J. C. Penney and Company in Lincoln, Nebraska. My goal was to become a manager in one of the 1500 stores. It was a good life. But the world was in torment.

The Sunday afternoon of December 7, 1941 was a lazy day. My roommate and I decided to attend a matinee movie. As we exited the theater building and were standing on the walk under the lights of the marquee, a newspaper headline caught our eye. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. We were at war.

The Christmas Season was upon us and I was busy on my job, but all the time I was mulling over my options. I was 20 years of age and had not received my draft card. In February I would be 21 – only a month away, which surely meant a tour in the Army. Early in January I had decided to join the Navy. On my lunch break I visited the Navy Recruiting Station. I was inducted a few days later in the larger facility in Omaha. I was ordered to go home and wait for orders. Early in February 1942, orders arrived. Destination: the Navy Boot Camp in San Diego, California.

—————————–

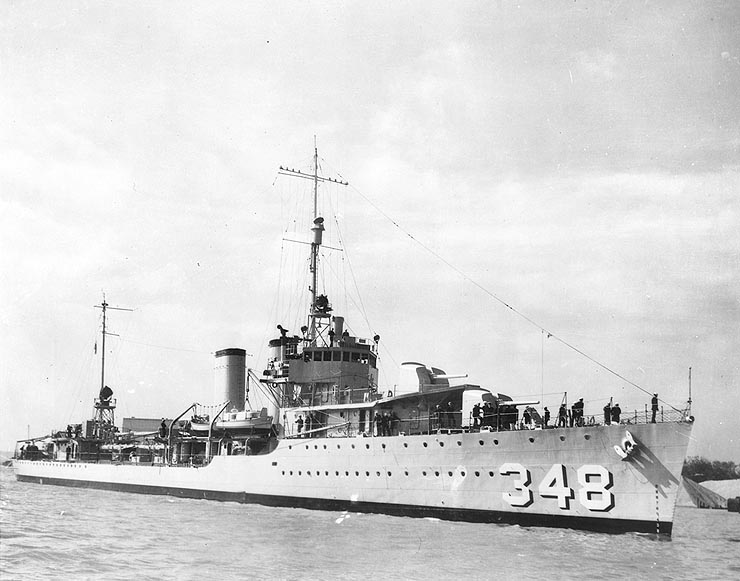

All of the above is merely a prelude to the real story. It is a story about a proud ship with a proud name in Navy annals: a U. S. Navy ship, the FARRAGUT (DD348), a destroyer by designation.

The FARRAGUT was launched at the Fore River Shipyards, Quincy, Massachusetts on June 18, 1934. She was a two-stacker, the first built of that kind. Seven other destroyers were built with their own names, but after the fashion of the FARRAGUT. They were considered to be of the FARRAGUT “class”. During her commissioning run she broke all existing speed records by attaining a speed of 39.6 knots.

She was the proudest in the fleet before hostilities. On two occasions Franklin D. Roosevelt used the FARRAGUT for pleasure on fishing trips in the Caribbean. The ship was moored in Pearl Harbor the morning of December 7, 1941. Prior to my coming aboard in October of 1943 she had been operating in the Coral Seas and the Aleutians. After some research, it is believed that the FARRAGUT was engaged in thirteen major Pacific operations during the war.

My sea bag seemed extra heavy on my shoulders that morning in October of 1943 as I climbed the gangplank. Immediately at the head of the gangplank stood an officer all polished and unsmiling. After the necessary protocol, I handed him my orders. This “Tin Can,” all steel and iron, 30 feet wide and 300 feet long would be my home for the next 2 plus years. Soon a big guy with a fat belt line appeared with the words, “Follow me.” He escorted me down a ladder into the bowels of the ship where the enlisted men were bunked. “That is yours.” he said, pointing to a bed 2 feet wide and 6 feet long, hanging on chains and stacked at intervals of about 2 feet in vertical fashion. It was a dungeon where approximately 200 men had such accommodations to call their own. And thus it was. For the next three days I was an unnoticed entity, until that night at 22:30, when there was a tugging at my shoulder and a flashlight shining in my eyes with the announcement that I had the next watch, midnight until 4 a.m. Nothing had ever been said about a watch. But there I was, being led by a guy that I did not know, to a place that was a mystery. It was raining hard. I could hear voices. Pulling back the canvas that was a temporary shield from the rain and sitting inside the 5-inch gun turret were three ghost-like figures. Lights were not permitted at night, not even smoking above deck in the open. That was my introduction to life aboard ship. A life in retrospect of which I eventually became quite fond.

The ship was in San Diego when I came aboard. After a week of making practice runs, we set sail for an unknown destination. On the fifth day out, land was on the horizon. Drawing near, we dropped anchor. It was Maui. Liberty was not granted to the crew. The next day we were again underway. We passed over the International Date Line unnoticed and then the equator. In those days passing over the equator was a big event in the Navy. There were two classes of personnel on shipboard. Shellbacks were those who had at one time been polliwogs and had undergone the initiation and were now at liberty to show their superiority. The practice, as was then carried on, has been discontinued by naval decree as too many polliwogs were being hurt in the initiation process. I withstood the test. It was almost savage. A few days later we were anchored in Espiritu Santo, an island near New Zealand. The island belonged to Britain. We were granted a few hours of liberty.

The next morning, we were underway again with a number of other ships. The higher command for retaking the Pacific Islands had finalized a plan which would be known as “Island Hopping.” Japanese-held islands that were strategic to them for survival would be retaken, one at a time, until we had reached Tokyo. Tarawa would be the first such effort.

The FARRAGUT was a part of this task force to retake Tarawa. Our part was to lay off the island about 1800 yards and strafe the beach with 20mm gunfire and loft larger projectiles into the interior with our cannons. Many ships were carrying on the same effort. The battleships lay further out, about 15 miles, and bombed incessantly with their big guns. The Air Force was also flying over the island from carriers. This activity continued on for several days. The constant bombing had the purpose of softening up the enemy as the Marines would come ashore.

The islands we hit were always covered with large numbers of palm trees. Having grown up in Iowa, the palm trees broken down into stumps reminded me of seeing corn fields being nothing but stubs after a hailstorm. It seemed impossible that anyone could be alive, yet when the Marines landed, the enemy hoards came up out of the sand. It was never easy for the landing forces no matter how much bombing was done. I so admire the U. S. Marine Corp.

Another problem arose in this first attempt at island hopping. Many of these islands had coral reefs. These reefs made landing difficult, which slowed the invasion and caused many fatalities. Tarawa was finally equalized, but at a heavy price.

She had carried out her orders at Tarawa. The FARRAGUT was ordered back to San Francisco. After a few days, we sailed down the coast to San Diego. With new orders, we were soon on our way even deeper into the hostile fighting. Our destination was the Marshall Island group. The FARRAGUT’S commission was the same: that is to provide support and cover for the invading troops. The Marshall’s consist of a number of islands. The FARRAGUT was active in retaking Kwajalein, Eniwetok and Majuro.

In April of 1944, we joined up with another task force, Destination New Guinea, where we participated in the Hollandia strike. Moving on from New Guinea, the FARRAGUT bombed and strafed several islands, which included Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Truk.

Truk was somewhat different from most of the other islands, which were generally flat and sandy with dense coverings of palm (coconut). Truk, by contrast, had high mountains which surrounded a bay. Because of the formation, it was an important Japanese shipping point. Our planes were unable to swoop down and drop bombs. The FARRAGUT was patrolling the open sea nearby. Several Japanese ships had been sunk and the area was covered with flotilla. Patrolling, we came upon a raft and three Japanese survivors clinging to this raft. The FARRAGUT pulled alongside and motioned for them to come aboard. Despite their poor physical condition, they refused and waved us on. As a last resort, our executive officer had to enter the water and pull them alongside, where we manually took them aboard. They remained difficult throughout the ordeal. They were offered showers and food. The food was refused. The FARRAGUT had no facility for keeping prisoners. They were moved onto a larger ship. The same situation occurred a little later in the day with one survivor. The response was the same.

The next assignment for the FARRAGUT was the liberation of the Mariannas. The mission was the same as in the taking of other islands. The targets were Saipan and Guam. At this time the FARRAGUT came under the command of Lt. Commander C. C. Hartigan, Jr., USN.

Please allow me a parenthetical observation at this time. Because of my watch station assignment, I spent considerable time on the bridge. The radar screen was accessible. When we were underway on missions, it was almost breathtaking to see the number of ships travelling in unison. I always felt a lot of comfort in that.

It was December, 1944. Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet was operating in the China Sea. The convoy of ships had been split into two groups. The FARRAGUT was the only ship of the FARRAGUT class in one group, while in the other group the HULL, MONAGHAN and DEWEY of the FARRAGUT Class had assignments.

When in enemy waters, it was customary to transfer fuel into the various ships, so that each ship would have enough fuel for five days if it were separated from the fleet. That refueling process was being carried out when a typhoon moved in on the fleet. The typhoon named “COBRA” lasted several days and went down in Navy records as one of, if not the worst, of all storms confronted by Navy ships. The FARRAGUT was in the midst of this tragedy in which the HULL and MONAGHAN capsized and the DEWEY was badly damaged. Several other ships capsized or were badly damaged. The loss of men was almost 900 young sailors. The FARRAGUT righted after taking a wave that sent her rolling and shuddering. At times we were in a valley surrounded by water. At other times, the fantail of the ship would be high on a ridge of water and the propellers spinning madly in the air. Everything on board was shut down. It has been estimated that some of the walls of water forming these valleys were 100 feet tall. As the storm subsided, the FARRAGUT was ordered to nearby Ulithi, where we spent Christmas.

After a short respite in Ulithi to celebrate Christmas and make repairs after COBRA, the FARRAGUT and MACDONOUGH were ordered to the Philippines. The Philippines were being liberated. The fleet was anchored in Leyte Bay. At the west end of the bay were high mountains. It was early evening with the setting sun just showing over the mountain peaks: the perfect time and conditions for the Japanese to attack. I remember so clearly, one lone plane coming down from behind that mountain and blotted out by the sun. The plane swooped down and passed through the entire fleet of ships with not one retaliatory shot being fired. The plane had come in so low that to have done so would have put our own ships at risk.

At that time, the FARRAGUT, the MACDONOUGH and several other destroyers were given a special assignment. Looking back, it must have been a reconnaissance mission, looking for Japanese ships that may had been hiding in the many little bays in the Philippines. As a result of the mission, the FARRAGUT, along with the several other destroyers, were the first of our ships to pass around the tip of Luzon, into the China Sea and through an east/west channel in the Philippines. The natural channel zig-zagged through the island. My little black book that I kept of events, if only notes, tells me the channel was known as the Surigao Strait. It was a beautiful way to see the interior of the Philippines.

After the Philippines, the FARRAGUT was assigned several different sorties around Eniwetok. On February 9, 1945, the FARRAGUT left Ulithi to participate in the landing of Iwo Jima. At this time there were beginning to be signs of the defeat of Japan, although it was still six months away.

The FARRAGUT had been in Ulithi for a short time, when orders were received to proceed and aid in the Okinawa campaign. The war’s end was within sight. Hostilities had ceased in Europe. Okinawa was at the very doorstep of the Japanese homeland. When our ships began to arrive at Okinawa, they came under the attack of the kamikaze. Many of our ships were damaged. It was a last ditch, frantic effort to stop our march into Tokyo. Seeing the carnage and death tolls at Okinawa, the atomic bomb, as horrendous as it was, saved many lives. I remember on the passage through islands enroute to Okinawa, how the remote countryside seemed to fulfill the beauty of the far away Japan that I had learned about in grade school. The FARRAGUT had come to anchor in Hagushi Beach in Okinawa. The passage getting there was through the Kerama Retto Islands. The countryside in those islands was at peace. The hills were terraced and painstakingly farmed. The beaches were white sand.

The end came with the dropping of the bomb.

The process of discharging personnel and retirement of equipment began immediately. There being no computers in those days, all paperwork was typewritten. The FARRAGUT was ordered back to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. On the return trip we were welcomed home in San Diego. Then it was on to the Panama Canal and liberty in Panama City. On our arrival in Brooklyn, it was learned that the proud servant to her country would be sold for scrap. The rumor was that she was sold for $1500. By November of 1945, only 4 short months after the cessation of hostilities, the mighty FARRAGUT had been decommissioned and her crew was on one month’s leave and would be civilians by February.

DF